By James Ren

Originally published June 14, 2021

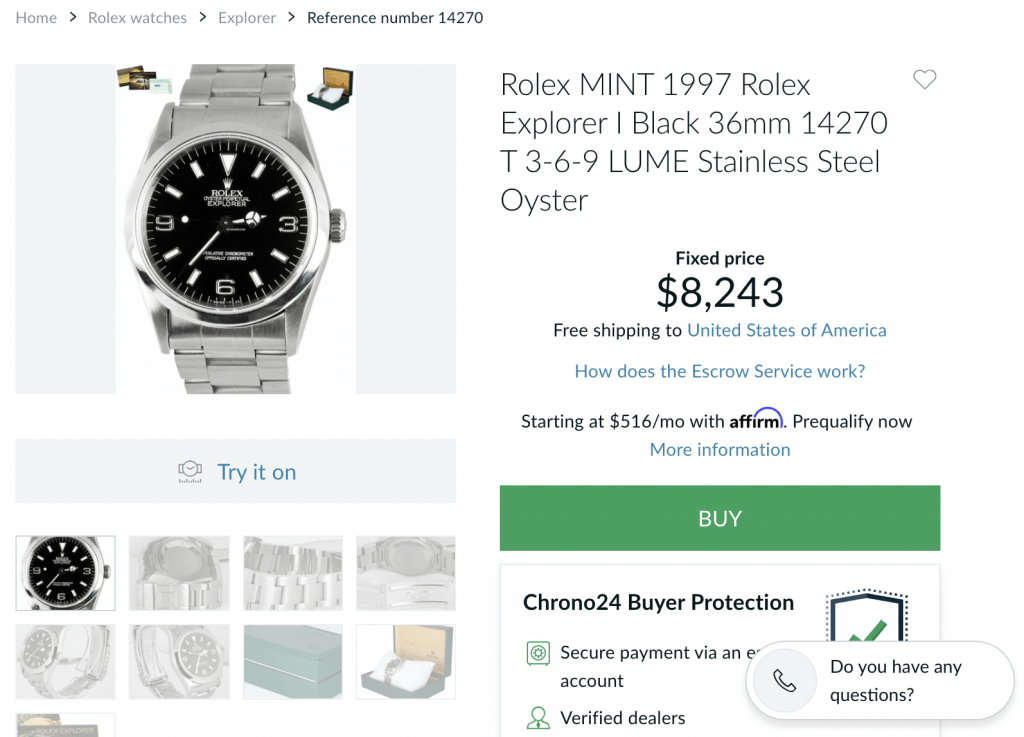

The Rolex Explorer 14270 (1989 – 2001) has always been a laggard in the vintage Rolex sports model scene. A rising tide lifts all boats, and its price has risen recently. However, it has lagged behind other models, including the preceding 1016 that ran from 1963-1989. The potential for aging of the tritium lume on the dial has boosted the 14270 past its otherwise superior successor in terms of construction and movement, the Explorer 114270 (2001-2010). In the past few years certain influencers have advocated for the 14270 as the affordable Rolex sports model, ironically making it less affordable. It therefore seems to be a good time to examine this issue. Full disclosure: I own the Rolex Explorer reference 114270 (2001-2010).

Who Is Walt Odets?

I had the pleasure of speaking to Walt Odets. He is easy to find on the internet despite not participating in watches anymore. He is, in fact, a clinical psychologist who is well-known for having worked with gay men during the early AIDS epidemic and has authored several best selling books on the subject. In the watch world, he was a major figure in the heyday of watch forums prior to the rise of watch blogs. He has had a knack for tinkering since he was a child, and his writing was known for its obsessive attention to detail, especially regarding movement finishing. As an amateur, he taught himself to disassemble his watches to understand, photograph, and critique them. A man of genuine passion for watches and not motivated by financial concerns, his critique of the Rolex Explorer 14270 on Timezone should be taken seriously even though it was first published in 2002.

Synopsis

Odets first placed the Rolex Explorer 14270 in context as a watch in the “lower-middle segment of the stainless steel line…without date, retailing for approximately $2,500…also perhaps, the most historically connected model…deriving from a long line of very similar Explorer designs.” I find this perspective refreshing because it cuts right through the hype. He acknowledges the history but notes that it is a time-only watch that is only distinguished by the design lineage from the low end Oyster Perpetual.

Odets then discusses the case. He has some quibbles about the finishing on the backs and inside of the lugs but also describes the case as “an unusual, peculiarly appealing double-horn shape characteristic of many Rolexes, and are sumptuously polished so that the metal has almost the luster of white gold.” So not all bad!

Interestingly, Odets’ problem with the dial is more the design than the finishing. “To my tastes, the markers and hands are oversized and give the dial a cramped and busy appearance…Taste aside, the dial and hands are detailed, extremely well made, and immaculately finished.” I think the design issue remains fair game and is the basis for the preference of the 1016 but the 14270 dial has withstood the test of time and remains more or less unchanged today.

Odets was rather disappointed by the bracelet, noting that “For a watch that is in some ways about its steel bracelet, it is remarkable that this bracelet looks so much like an after-thought.” He does not like that the bracelet is not integrated and harshly criticizes the hollow end-links as fitting the case “very crudely, following neither the contour of the case, nor the legs. The design and fit is as awkward and unattractive as anything I recall seeing on a production watch. The clasp for the bracelet is comprised of stamped steel pieces that feel cheap.” Although his criticism is harsh, it is fair as evidenced by the fact that Rolex upgraded to solid end-links in the next generation, the 114270 (which I own).

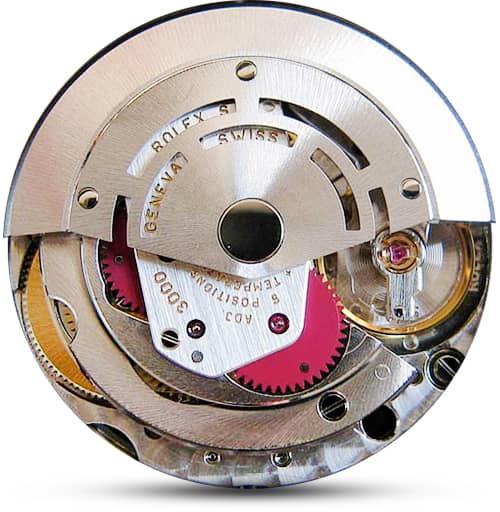

The Movement Part I: The Good

The movement is where Odets really comes into his own as a critic. His highest praise is for the automatic winding system which he notes is well-finished and a good design. He does note that the rotor shaft is not very well secured to the automatic winding bridge, which leads to wear. He notes that this is a common issue at Rolex service centers. Other features he points out are the non overcoil hairspring and a Microstella balance. He makes some comparisons between the Microstella balance and Patek’s Gyromax, which is a similar free-sprung balance where the regulation is done by adjusting screws on the balance wheel rather than the length of the hairspring. He notes that the Patek Gyromax allows for screwdriver access from above, making it easier to regulate.

I really appreciate the level of detail and knowledge that allows Odets to make this kind of analysis. I would contrast his analysis of movement design with the current trend of analyzing only the dial in order to draw distinctions between watches. Anyone with a computer screen and enough time can point out differences in dials, but analysis of movement architecture is sadly lacking in today’s watch writing. Mechanical consideration may be a bit boring, but it is really fundamental to understanding what makes a good watch. The main principle is that friction is the enemy.

The Movement Part II: The Bad and the Ugly

Odets notes that the performance on the timegrapher, aside from a few quibbles, is good. However, he then heads into a devastating critique of the quality of the movement. His description of the Caliber 3000 is that it “is obviously engineered for minimum parts count, easy assembly, and economy of manufacture and service. It is an extremely simple movement by design and I imagine it could be produced in a workman-like way at a cost equal to or below that of some of the most inexpensive automatic movements in current production…The price of this watch-and the Rolex reputation-left me entirely unprepared for the number of shortcuts that had been taken in the actual production of this movement,” Odets asserts.

The “shortcuts” taken to maximize production efficiency in the Caliber 3000 are the heart of Odet’s criticism of the Rolex Explorer 14270. These compromises are comprised of money saving manufacturing processes that add friction to the movement. He notes that the holes for the jewels have unfinished edges with machining debris that is evident on the edges as well inside the movement. Odets also noted poor finishing on a screw which gouged the plate and caused some debris to form. He provides a litany of other quality issues including poor finishing on the balance wheel and screws, sloppy oiling, “the mostly [sic] crudely finished escape wheel I have ever personally seen in a watch,” straight instead of epicycloidal teeth on the escape wheel, and rough edges with excess metal on the mainplate. His commentary on the decoration is similarly harsh, describing it as “The few attempts at surface decoration seems ridiculous in this context, and these attempts are, unfortunately, as badly executed as the rest of the movement.”

Odets caps it off with, “Such pretentions to “fine finishing” seem ridiculous – or merely cynical – when so badly applied to a movement of such poor basic quality. The money would have been better spent on pragmatic finishing that eliminated contamination inside the movement and other very basic work that raised the movement to an acceptable minimum level of functional workmanship. As it stands, this caliber 3000 is the most crudely finished watch movement that I have ever personally examined; and I include in that observation, a number of movements in extremely inexpensive watches.”

In discussing his personal conclusions, Odets notes the paradox of a watch “so lacking in basic workmanship is capable of being so accurately timed” which he attributes to loose tolerances allowed by the thickness and computer-timed balance assembly. He notes that the industrial mass-production methods of Rolex mean that the watch he examined must represent Rolex’s current quality since many others are assembled in the exact same fashion each year. Odets concludes that the Rolex is very overpriced and suggested a retail value of $600-800, a far cry from the current pricing and declares it “of no horological interest whatsoever” and states that “I cannot think of another consumer product in which the gulf between the publicly perceived quality and the reality I saw is as broad as with the Explorer.”

Analysis

What conclusions can we draw from Walt Odets’s commentary? Is his critique as devastating today as it was almost 20 years ago?

My first thought is that watch collectors have changed. Ironically, as display casebacks have proliferated, the monomaniacal attention to movement finishing remains in decline. Today’s collectors are largely interested in dial variations and patina rather than the movements. The tritium lume, of the 14270, which will turn a creamy vanilla color over the course of a couple decades, has boosted it in price compared to its successor, the 114270, even though the later model has an improved bracelet with solid end-links and an upgraded movement. For a more recent example, contrast the hype over the Oyster Perpetual “Stella” dial watches with the yawn that followed the announcement of a Rolex Explorer II being released with minimal cosmetic changes with the main update being an upgrade to the Caliber 3285.

I think that, taken in a literal sense, Odets’ criticisms are valid. The best evidence is that later iterations of the Explorer 1 have gradually upgraded many of the flaws which he pointed out. His deep knowledge and appreciation of watchmaking allowed him to predict the improvements. I suspect that the upgrades were made as the computerized and robotic engineering necessary to produce these watches at an industrial scale became available.

I also think that the kind of movement quality appreciated by Walt Odets hails from an earlier time. The Rolex Explorer 14270 with its Caliber 3000 represents the end of a transition from an artisanal method of watch production to an age of industrial and computer engineered processes. Computer aided design methods and engineering expertise allowed movements to be made more cheaply without sacrificing performance. The traditional criteria of hand polishing to remove any trace of friction was being superseded by computers that engineered the problem away. Movements were becoming thicker, more accurate, more robust, but also less beautiful. In reality Walt Odets was looking at the future of watches and he didn’t like what he saw. Ironically the industrial methods of that time should have made mechanical watches cheaper and more accessible, but marketing hype has driven the prices to an astronomical level. Perhaps it is not the Rolex Explorer 14270 that has changed, but our perception of it.

For the full text of Walt Odet’s critique of the Rolex Explorer 14270 on TImezone, click here

For a modern view of the Rolex Explorer 14270, click here