“I think there’s nothing wrong in buying things you can love-and God knows that people do have strange tastes-but my advice is to buy those things because you love them, not because you expect them to appreciate in value.”

-Burton G. Malkiel, A Random Walk Down Wall Street

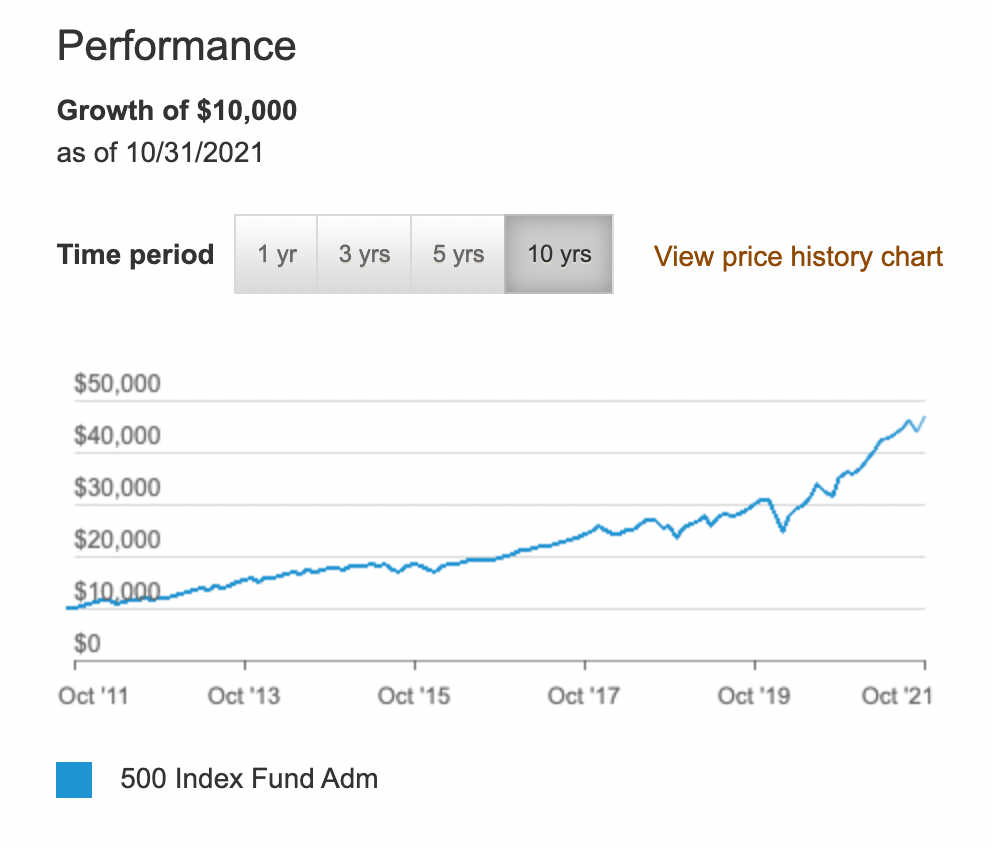

To evaluate whether watches are a bad investment, I think we need to consider the purpose of an investment and how it accomplishes that purpose. A classic, boring example of a conservative investment is an index fund. This allows the investor to buy a portion of a portfolio of stocks in a broad financial index with low management fees and broad diversification. It’s the kind of thing that sits in a retirement plan, slowly hitting singles over the years without ever hitting a home run. However, with the magic of compound interest, an investment of $10,000 over a 30 year period will turn into about $100,000 with the historical average of an 8% return per year.

So in other words, an investment is an asset that you purchase in exchange for cash that you can sell for more cash later on. Now does buying a watch accomplish these goals? Certainly there are examples of certain watches which have greatly increased in value over time, such as Paul Newman Daytona. But I think it’s helpful to think about what buying and then selling a watch actually entails from a financial point of view.

Let’s consider the acquisition of an asset. An index fund can be purchased with a brokerage account. It has an easily visible market price and no transaction fee. Later on, it can be sold very easily, for a market price at the time of sale, with capital gains tax applied to the profit. Buying and selling a watch, on the other hand, is far more complicated.

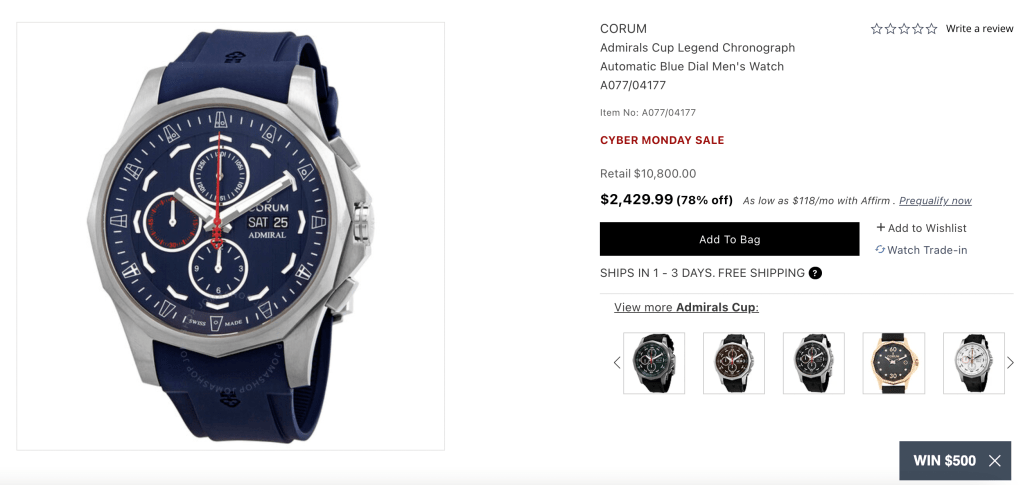

First of all, picking a watch is not a very straightforward task. Presumably you want to buy the watch to enjoy, not purely based on the expectation of monetary gain. This means that the watch you want may not be the best investment piece. Furthermore, how do you know which watch will appreciate in value? For every Paul Newman Daytona, there is a Breitling Avenger, or a Corum Bubble, or any of a host of other watches which have gone out of style and are worth very little today compared to their sale price. As a stock prospectus will tell you, “past performance is no indicator of future results.” If you can pick the right watch every time, then you can probably make a good living as a fortune teller. Essentially we are dealing with a highly speculative market with rare big rewards but also significant potential for big losses.

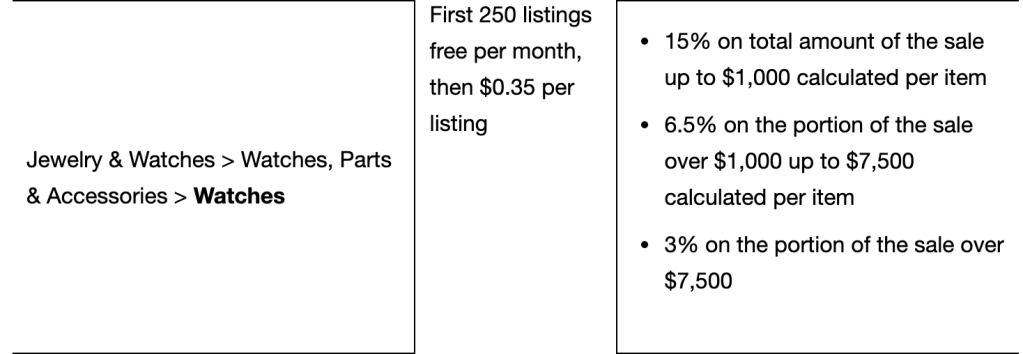

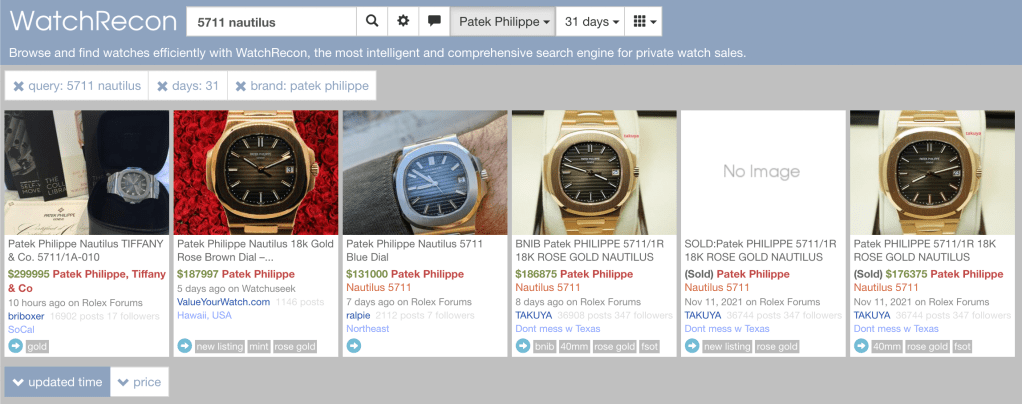

Once the watch is chosen, finding a fair price is not very straightforward. In other words, the market is opaque. Although in this internet age it is easier to find sales data though eBay sold listings or auction results, as a customer you will not have access to dealer prices. Remember that the seller does not receive the full price of the sale because the auction house or online marketplace receives a significant percentage of the sale.

Consider where you will buy the watch. Will you buy the watch from an authorized dealer in a physical store? Then you need to pay a premium in order for them to pay their rent, their sales staff, and for them to keep the lights on. What about from an online dealer? The dealer still needs to sell for a premium over what they paid plus their expenses in order to turn a profit. Scouring the watch forums to try to buy from a fellow collector may yield a better deal in exchange for more risk in terms of whether you can get a refund if the watch is not as expected.

The asking price for watches is also often not the selling price. How much are you willing to negotiate? In other words, unless you are a dealer with access to dealer networks, buying a watch has significant transaction costs related to the need for the seller to make money which can be as high as 25-50%. Imagine that you are paying $10,000 for shares of an index fund but there is a $3,500 fee so that the shares you receive are only worth $6,500. This is essentially what happens when you buy a watch. In order for you just to make your money back, never mind make a profit, your watch needs to increase in value by whatever premium you paid before you make even a penny.

Owning the watch is not without risk and costs as well. Presumably you will want to wear the watch. This exposes it to potential for losing it in a hotel room for example, or having it stolen. Want to insure your watch against loss? Then you are paying the insurance premium and losing money each month instead of gaining a dividend or interest on your investment. Want to store it instead of wearing it? Then you are paying for the storage fees by buying a secure safe at home or paying for a safe deposit box.

As it is worn, it also undergoes wear and tear to the movement and case. Swing it hard into a doorjamb and you may find yourself taking a significant loss if you want to fix a dent in the case. Take it swimming with the crown unscrewed and you may find yourself with a hefty watchmaker’s bill. And like a car, eventually the watch will need servicing which may be quite expensive as well.

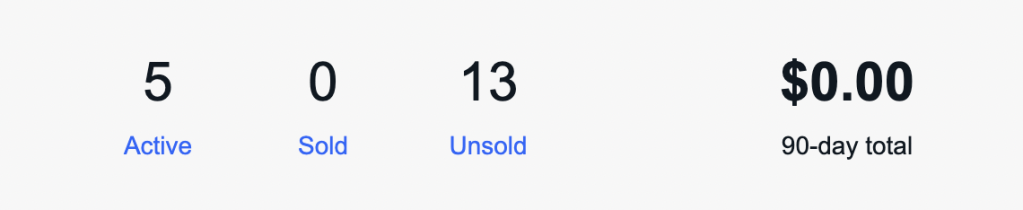

Once you decide to sell the watch, then you face a whole other dilemma. A stock is sold on an exchange for a market price. The watch you own needs to be sold to someone who wants that specific watch, so the market may be limited. If you want to sell quickly, you may need to lower your price by selling to a dealer who will want it for as little as possible, or by listing it on an online marketplace like eBay or Chrono24. Keep in mind that online marketplaces will have a fee that amounts to 10-13.5% of the transaction and a United States buyer will typically need to pay sales tax as well. So the liquidity is generally inversely proportional to the price and thus inversely proportional to your return on the investment.

So in a watch purchase you have an item which is bought with a high transaction fee, has significant risk of loss or damage during its ownership period, has high maintenance, insurance, and storage costs, and is potentially difficult to sell, especially if you want to turn a profit. Although you will be able to get some money out of a good watch when sold, it probably is not as much as you may imagine. In my opinion, the idea of “watches as investments” is a sales pitch from dealers who are looking to get you to part with your hard earned cash, and wishful thinking on your part as someone who likes watches. The bottom line is that you should buy watches for pleasure with a prudent amount of money you can afford to spend, not as an investment.

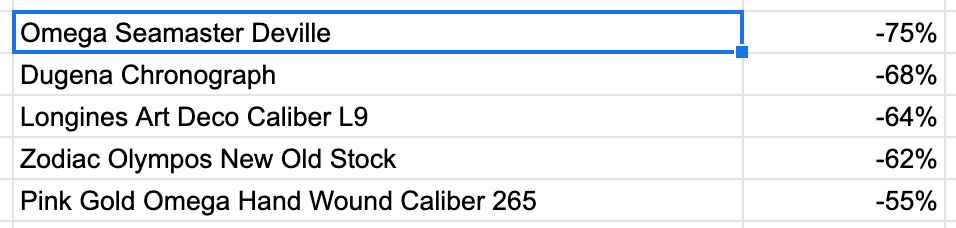

In surgery, we have a culture of what we call “M&M” which refers to morbidity and mortality rounds. Once a week, the entire department gets together and discusses everything that went wrong in order to find out how we can improve. In that spirit, I would like to share some of my biggest losers.

I will say this in my defense though. When I bought these watches, there was something I genuinely loved about them. When I sold them, there was something I had discovered that I didn’t like about them. So it seems natural that I would be willing to pay more when I bought them and be willing to sell them for less. Perhaps my financial losses are proof of my passion for watches after all.

I will leave you with another quote from Burton G. Malkiel about investing in collectibles.

“To earn money collecting, you need great originality and taste. You must buy first-class objects when no one else wants them, not inferior schlock when a vast uninformed public enthusiastically bids it up. In my view, most people who think they are collecting profit are really collecting trouble.”

I agree with you to a point. You will probably never make money on watches, but a decent collection can be a useful liquid asset for emergencies. There are very few other goods that you can sell for 60~70% on the dollar.

A used Seamaster professional goes for about 3k, and will for the foreseeable future. You won’t make a profit, but if you needed a month’s cash on the spot there are few things as liquid.

LikeLike